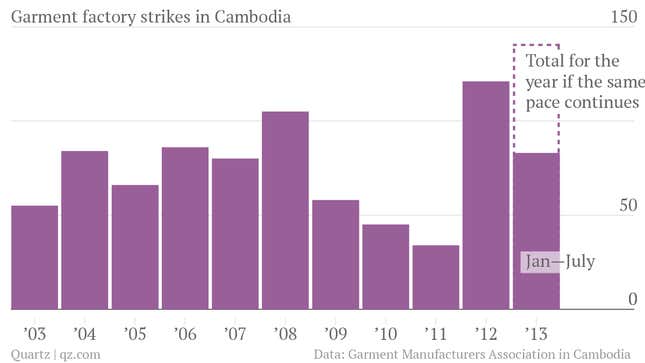

From January through July of this year, Cambodia saw an average of two to three garment industry strikes a week, adding up to more strikes in those seven months than in entire years in the recent past.

Just today, some 4,000 workers marched on the capital to protest against SL Garment Processing, a Singapore-owned company that workers claim has unjustly fired its employees in the midst of an ongoing strike. If the pace of striking continues, there will be some 140 by the end of the year, the highest number since Cambodia’s Garment Manufacturers Association started tracking strikes in 2003.

Garments are Cambodia’s biggest export, and the industry employs hundreds of thousands of workers. Like those in Bangladesh, where some 1,100 workers died in the collapse of a garment factory in April, Cambodia’s factories have structural problems. For example, a collapsing roof at a Cambodian shoe plant killed three in May. But for the most part, striking workers have been protesting to demand higher wages and, in the strike that prompted today’s protests, to end to workplace intimidation.

Why now? The drivers of labor unrest in any country are typically tangled and deep. But a recent report (pdf) by the International Labour Organization highlights a few trends that are surely making the situation worse in Cambodia.

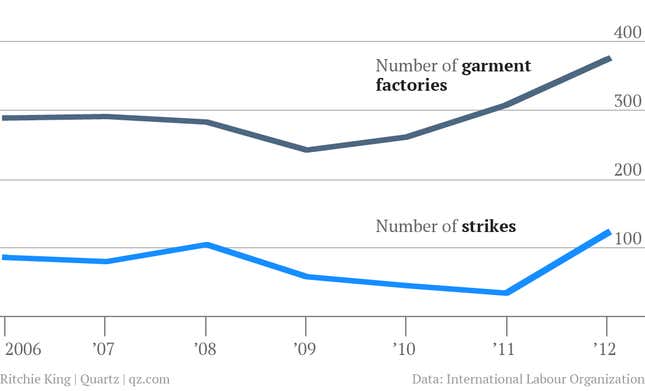

The industry is growing fast, and more workers means more strikes.

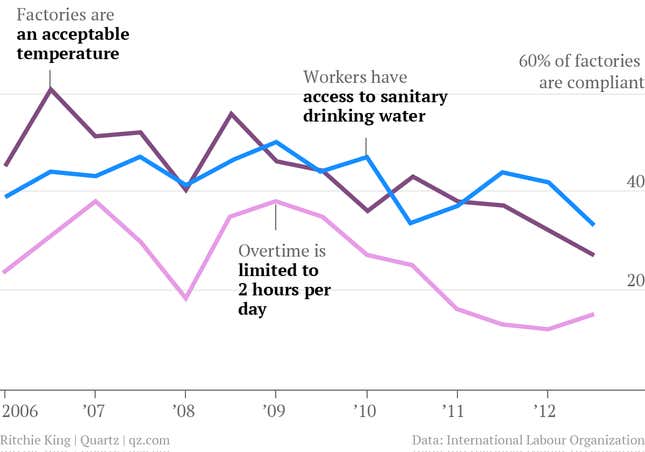

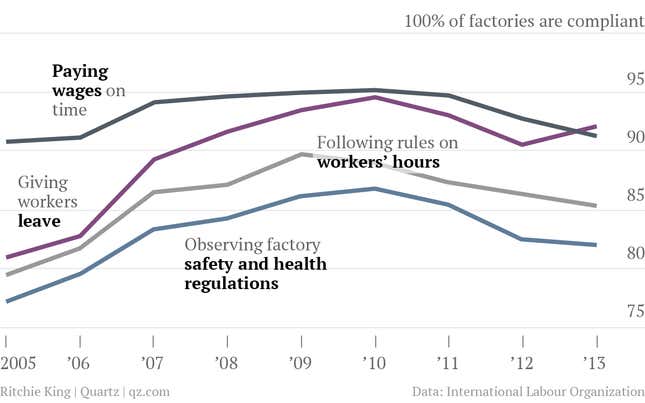

Factories are increasingly skirting regulations…

… especially those related to factory safety and humane working hours.